when i was auditioning, there was a new word invented among conservatory-level percussionists (and maybe other musicians): “nails”.

if you played an audition, and afterwards you said to your friends that “firebird was nails,” it meant you that you played the firebird excerpt exactly how you wanted it to go. you nailed it. and the idea was that if you nailed every excerpt, then you’d probably advance.

this obsession with nailing it was pervasive among my auditioning cohorts. it was my obsession too. we were all trying to be perfect. we didn’t know exactly how to achieve perfection, but we were all trying to figure it out.

but what does "nailing it" actually mean?

does it mean following every direction written on the page?

well… sort of. the audition committee has the music right in front of them during the audition. if you’re missing accents or not following dynamics, it might sound like a mistake.

but should you play the excerpt like a computer plays a MIDI file?

...no. then you’d sound awkward and unmusical.

remember that your audience is made up of human being musicians on the audition committee. they want to know that you’re going to play at a high technical level, follow the directions written on the page, and ALSO that you’re a creative, musical, and emotional player who can bring a unique personality to the music.

if you’re going to pursue only technical perfection, you’re going to get beat in auditions by more musically mature players.

on the other hand, if you’re a super creative musician always thinking about phrasing, tone, and character, but you ignore the pursuit of technical perfection, you’re going to end up with a sloppy performance that also doesn’t succeed.

instead of perfection, pursue precision.

you might feel like technical perfection and musicality are opposites, right? like if you’re going to add phrasing, but it just says “mezzo forte” for a bunch of measures, then you’re breaking the rules, right?

here’s the thing. when you play music, there’s so much finesse and detail that goes into the notes that can’t be written down. even when you’re playing straight 8th notes, there are slight ups and downs that i call ‘inflections’. you go TO the next downbeat. and when you get there, you… FALL away from that downbeat.

there’s always tension rising and tension falling. there’s phrasing on a micro-level, like when one note leads to the next, and there’s phrasing on a macro-level, like when an 8 bar phrase culminates in a climactic ending.

your goal in preparing repertoire for auditions isn’t to translate exactly what’s on the page in a mathematical way to the ears of the listeners like a robot would. it’s to develop a natural interpretation of the music and deliver that interpretation precisely.

you’re not painting by numbers. you’re not JUST following the directions written on the page. you need to build a thoughtful musical vision, and figure out how to precisely convey that deep musical vision to the committee.

ok…. that sounds a little bit impossible. how do i do that?

in my audition preparation process, i go through multiple steps between the time i get the music and audition day in order to thoughtfully and methodically develop my interpretation. in today’s blog i want to lay each step out for you so you can incorporate musicality into your own audition preparation process.

the first step happens before you even step into the practice room. if you just dive into the practice room without listening or thinking about your interpretation at all, you’re going to let the written version of the music decide your interpretation. it’ll sound like you’re just playing the black and white notes on the page… because you are.

you need to have an understanding of those notes as music. if you understand the music as an emotional experience first, then you’ll be ready to start practicing.

want to try 5 of my main practice techniques for audition prep?

it includes an exercise focused on each of the following musical elements:

time: the ‘wait for it…’ exercise

rhythm: the ‘where’d that come from?!’ exercise

phrasing: the ‘peaks and valleys’ exercise

dynamics: the ‘synesthesia’ exercise

musicality: the ‘3 emotion word’ exercise

step 1: study the composition itself.

get the score, the part, and a recording. listen to the recording repetitively and think about musicality. ask yourself these questions:

what is the phrase structure?

is it written in 4 bar phrases? 16 bar phrases? maybe a little of both, at the same time?

what is the chord progression?

if you understand the chords, you can start to understand when emotions are rising in tension and when tension is releasing.

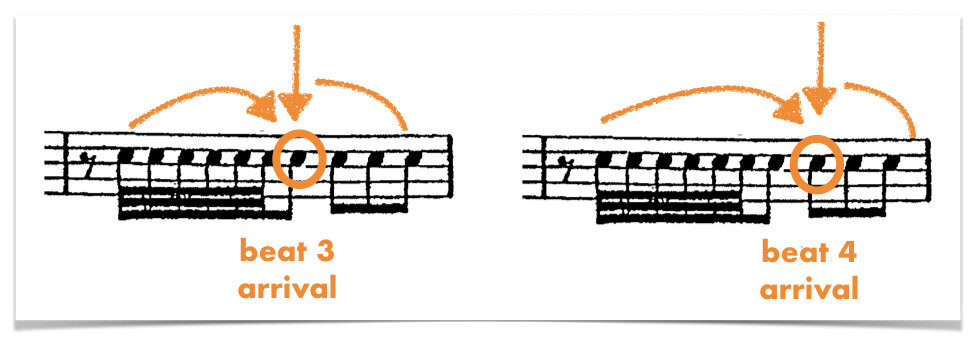

which is the “correct” arrival beat in this scheherazade snare drum excerpt?

what are the important “arrival points”?

you’ll build your phrasing ideas around these points. does it “go” to beat 3, or beat 4?

what’s the orchestration while your excerpt is happening?

you’ll build your tone to match the character and the texture. when you change your instrument tone from one section to the next or one excerpt to the next, the committee will hear the character of the music more clearly.

step 2: study the recordings

once you’ve studied the actual composition, then you should listen to a whole bunch of different recordings to see how various orchestras have answered the questions that came up during the last step.

you also want to understand the range of what’s “acceptable” so you have more confidence that your interpretation will be received well by the audition jurors on audition day.

i usually write out all this information into a huge document so i can reference it later.

here’s what happens next. after i’ve done excerpt research, all this information is spinning around in my head. i have a lot of ideas on how i can interpret the piece. but usually i’ll have an idea of what my current best phrasing plan should be, at least to start with. i know it’s going to change later, but i’m ready to actually go in the practice room and “install” that version into my muscle memory.

step 3: learn the notes

although you’ve come up with an ideal interpretation, you haven’t figured out how to execute it on your instrument.

at this point i’ll go through the music, measure by measure, and learn the notes.

each measure will involve some experimentation.

you’re translating your musical ideas to an instrument-specific execution plan. to match my musical vision, how tightly should i hold onto the sticks? where on the drum should i play to make the tone i want to produce?

each measure also involves repetition.

how many times do i need to play it before i feel like it’s easy and muscle memorized?

when you learn the notes, you’re learning an initial version of the excerpt. it’s enough so you won’t be embarrassed playing it for your teacher or for your friends. and it’s the best you can do so far, but you can still make it so much better.

step 4: record yourself

this is when i really start to experiment. i’ll set up a microphone and record myself so that i can hear how i would sound to the committee from a distance. and rather than play it in exactly the same way that i muscle-memorized it, i’ll start experimenting with everything i can think of.

how should i shape the phrases?

when rising in tension, is it a straight diagonal line? is it a trumpet bell curve??

how much can i exaggerate the shapes?

if i exaggerate too much, it sounds like i’m not following the dynamic directions. but if i don’t exaggerate enough, it sounds too flat and boring.

what can i do with the tone to convey character?

can i adjust my playing to contrast one section with another even more? what can i do with the tone to make it sound like this piece is the most “scheherazade-y” sound that’s ever come out of the snare drum?

how can i manipulate time to make it even more dramatic?

if you have a rubato or a cadenza, you can go crazy with this. but even if you don’t, and you’re trying to play exactly in time, you can still play a little bit on the front of the beat or the back of the beat to add certain colors to the music.

at this point i’m thinking about a microscopic level of detail. if it’s about time, i’m thinking in milliseconds. if it’s about dynamic, i’m thinking about tiny gradations of volume.

step 5: mock auditions

finally i get to see how my interpretation is received by others. in every mock audition, i’ll continue to experiment with each element of my musicality to make it even more dramatic and interesting to the listener. noa kageyama, performance psychologist and fellow teacher in our upcoming audition bootcamp, calls this “micro-improvisation.”

and i’ll also take comments from the mock audition listener to see whether something i’m doing sounds funny or wrong.

in fact, it’s important that i try to exaggerate my musicality to the point where it does sound wrong. i want to know how far i can go before i need to scale back a bit so that it hits the sweet spot of sounding musically effective and natural at the same time.

and then audition day comes around. but it’s never “finished”.

on audition day, you’ve refined your excerpts to the best they’ve ever been. you’ve done the most you possibly could do between the day you got your list and the day of the audition. but you’re never done experimenting as a musician.

your musical ideas should always grow, adjust, and evolve. it’s the same for me: i go through this intensive process of experimentation and refinement during my audition process, but there’s no right answer and each excerpt will evolve differently end up in a different place every time i take an audition.

this work you’re doing on musicality isn’t instead of working on perfection. in fact, the more refined your musical idea gets, the more it’s improved by being precise. if you can get the listener to stop thinking about how one note is slightly out of place rhythmically, then they’ll start listening to you more clearly in your phrasing ideas. if your phrasing ideas are interesting and you’re exactly delivering them in a precise way, you’ll be an unstoppable force in auditions.

“nailing it” should mean that you’re successfully conveying your complicated, layered interpretation of the music to the committee in exactly the way you want it to sound… not just playing it in the mathematically correct way.

ok, now it’s your turn.

what you need to build excerpts in this way is a system of practicing that addresses every element of precision and includes this experimental trial-and-error strategy that i’ve been describing.

if you’re interested in getting started, you can check out my phrasing strategy called the “peaks and valleys exercise” which is the third exercise in this download.

and if you’re interested in spending this winter working with noa and me to build an audition preparation system that allows you to perform confidently and musically at auditions, check out our audition bootcamp starting later this month. enrollment is open until sunday night at midnight.

in 2019, a cellist named maria reached out to me about her audition struggles. on paper, she was the “worst audition candidate ever” (her words). she had 2 small children, a full-time teaching job, and hadn’t taken an audition in 4 years.